I’ve been calling it the bingo machine.

You sit there watching the AI coding agent work. It stops. Asks permission. You hit allow. It stops again. Allow. Allow. Allow. You’re just pulling the lever waiting for the dopamine hit: the moment it finally says “done” and you can ship.

Then you actually test it. And it’s not done. Not even close.

Twelve months in

I spent the last year fully immersed in AI coding tools. Not casually—daily. I rotate through all of them, keeping only a monthly subscription at a time so I can switch to whatever’s state of the art. Cursor. Claude Code. Codex. Back to Claude.

I built an AI agent framework. I refreshed my Ruby on Rails knowledge after years away. I deployed to bare metal with Kamal. I shipped side projects I’d been putting off for years. The productivity gains were real.

But so were the failures. And after a while, I started noticing a pattern.

The agent’s definition of “done”

AI agents have a very different definition of “done” than I do. It took getting burned a few times to really internalize this.

I was working on a feature that seemed straightforward. A service needed to consume a Kafka event when content was published, convert HTML to markdown, store the result in the database, and expose it via a REST API. Four steps. Each one simple.

The agent built the API endpoint. Then it wired up the Kafka consumer. Then the markdown conversion. Each piece was clean, well-implemented, and worked on its own. The agent told me it was production ready.

I’d learned by then not to trust that. So I tested it myself. Actually published some content to trigger the Kafka message. Hit the API. Looked in the database.

Empty.

The pieces were there, but they weren’t connected. Four working components that didn’t work together. The agent had checked that each piece ran and moved on. It never tested the full flow.

This keeps happening. Not because the agents are bad at coding—the code is often quite good. The problem is how they’re trained. They’ve learned from vast amounts of software that works in isolation. Small services. Focused libraries. Code that assumes its consumers will figure out integration.

Real software isn’t like that. If you want to test the actual user value of a feature, you can’t work in one service alone. You need the whole stack running. You need to see the end-to-end flow.

AI agents don’t think that way. They work in small iterations, one piece at a time, and they’re remarkably good at declaring victory before the job is actually done.

What I do now: specs and progress tracking

I developed a workflow to deal with this.

Every feature starts with a spec. Not an automated test—a written document that describes what “done” actually looks like. What’s the user flow? What should happen at each step? What can I manually verify to know it’s working?

I keep these in a docs folder in every project. There’s a docs/backlog folder for features I haven’t started, and a docs/in-progress folder for whatever I’m currently building. When I kick off an agent session, I point it at the relevant spec. The agent reads the plan, understands the success criteria, and tracks its progress against it.

It sounds simple, but it changed everything. The agent now has a shared definition of done. It knows what I’m going to check. It can reference back to the spec when it gets lost. When I return to a session after walking away, I can see exactly where things stand.

The agent is still responsible for figuring out how to build the feature. I’m responsible for defining what success looks like. That division of labor works.

The environment problem

Even with better specs, I kept running into a deeper issue.

I wanted to let the agent run unsupervised. That’s the whole point. If I have to approve every command, babysit every file change, hover over every step—I might as well write the code myself.

These tools have two modes. The default mode stops constantly for permission. The agent asks, you allow, it asks again, you allow again. Bingo machine.

Then there’s YOLO mode. --dangerously-skip-permissions in Claude Code. --dangerously-bypass-approvals-and-sandbox in Codex. The agent runs free. It makes decisions. It tries things. It fails and retries. It figures it out.

YOLO mode is where the magic happens. But I couldn’t bring myself to use it.

Why? Because I was running the agent in my main development environment. Shared databases. Ports that might conflict with other work. State that could bleed across branches. One wrong command and I’d spend the afternoon untangling the mess.

Of course I didn’t trust it. The environment made trust impossible.

Managing their environment

One thing I’ve learned as a parent: if you want to stop saying “no” all the time, you manage the environment.

Hide the candy. Put the dangerous stuff out of reach. Childproof the cabinets. Once the environment is safe, you can say “yes” to almost everything. The kid gets freedom to explore, and you’re not constantly hovering.

AI agents are the same way.

The problem wasn’t the model. It was their environment. I was asking agents to work in a space that wasn’t set up for them, then getting frustrated when I couldn’t trust them.

The agents themselves are remarkably resilient. They’ll try dozens of approaches to solve a problem. They recover from errors. They find creative workarounds. If you let them run, they’re persistent in a way that’s genuinely impressive.

But if you constrain them too much—if you keep interrupting, limiting their tools, second-guessing every step—they start to fake it. They’ll tell you the job is done because that’s what makes the human stop asking questions. The more you micromanage, the more they optimize for appearing successful rather than being successful.

The solution isn’t tighter control. It’s a safer environment.

What I built

So I built what I needed. Piece by piece, over months.

The foundation is devcontainers. Not just Docker images—the full devcontainer spec. The distinction matters.

A Docker image is just a container. A devcontainer is a reproducible development environment. It’s actually several pieces working together:

- A Dockerfile that builds the base image

- A compose file that defines the container and any sidecars

- A devcontainer.json that configures the IDE, installs extensions, mounts volumes, and sets up dev-specific tooling

The devcontainer.json is where the magic happens. It’s what makes this a development environment rather than just a container. You can install devcontainer features—pre-packaged tools that get added at build time. I have one that installs my AI coding agents:

| |

I don’t install agents in the Dockerfile. I add them as a feature. Same with other dev-only tools. The Dockerfile stays clean—ideally reusable for production. The devcontainer handles everything specific to development.

A real example

Here’s the setup from a Twilio voice agent I built. The compose file defines two services:

| |

The app container is where I work. The cloudflared container runs alongside it, exposing the environment to the internet through a Cloudflare tunnel.

This means webhooks work. OAuth redirects work. Third-party integrations that need to call back into your app—they all just work.

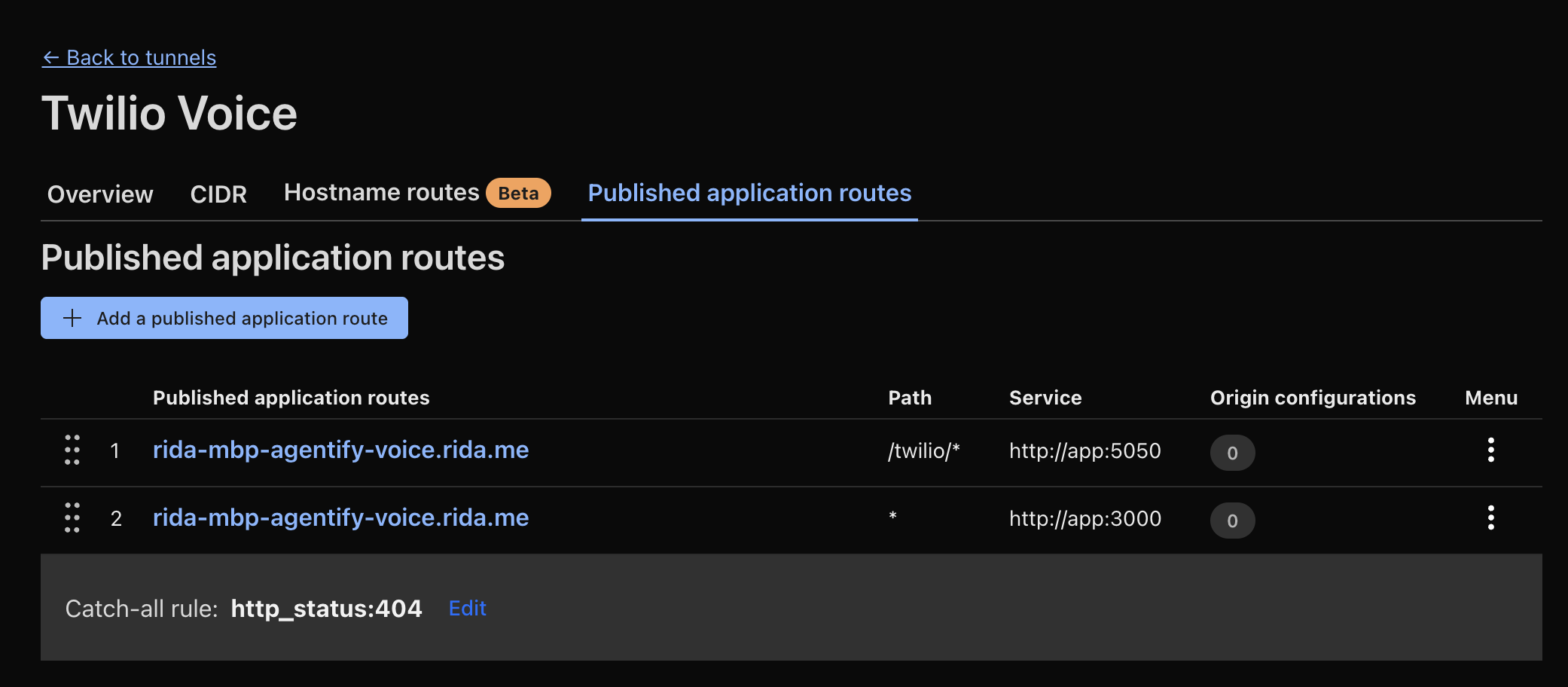

For this project, I needed both a user-facing UI on one port and a websocket endpoint for Twilio on another. With Cloudflared’s routing table, I pointed different paths to different ports:

Same hostname. Different paths. Different services. Could have been separate containers just as easily.

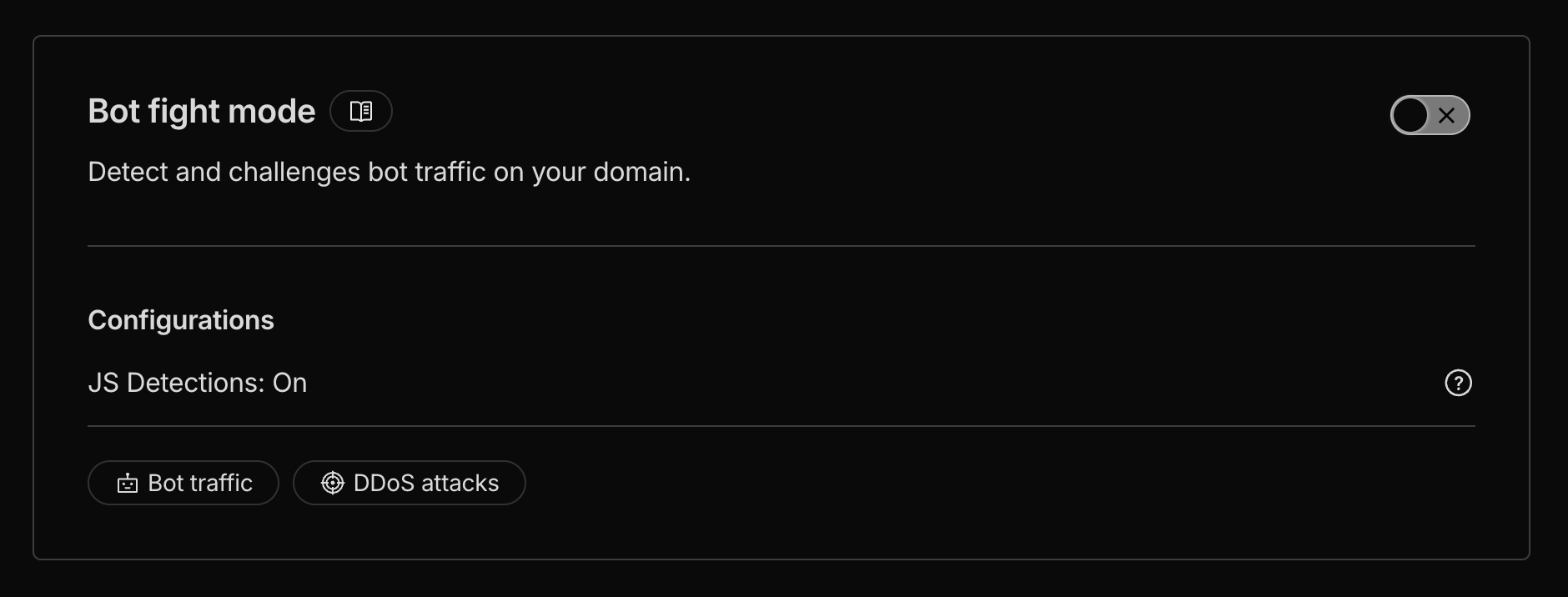

One gotcha: if you’re building anything that needs to interact with ChatGPT—like exposing an MCP server—Cloudflare’s Bot Fight Mode blocks it by default. You’ll need to turn that off:

Tunnels per branch

The real unlock was automating tunnel provisioning.

I use the Cloudflare API to provision a new tunnel for each feature branch automatically. No collisions. Each branch gets its own public URL. When I spin up a new feature, it’s immediately accessible from the internet with its own hostname.

This is what makes the isolated environment actually useful for real development. You’re not just running code locally—you’re running a full environment that behaves like production.

Secrets

For secrets, I use 1Password with a dedicated vault that I think of as a “team vault” for AI agents. I create service accounts and use 1Password Connect to inject credentials at runtime.

For destructive operations—git pushes, deployment keys—I keep those behind the SSH agent on my host machine. It prompts for biometric auth before those secrets are accessed inside the container. The agent can’t accidentally push to main without my fingerprint.

The mental model: treat the AI agent like a new hire. Give them their own credentials. Scope their access. Don’t share your personal keys.

Verification

The agent needs tools to verify its own work.

I use Playwright. The agent can spin up a browser, navigate to the feature it just built, click through the UI, take screenshots, and check that things work end-to-end. Not “the code compiles.” Not “the tests pass.” Actually: “the user can do the thing.”

This matters because agents are trained to declare success. If you don’t give them a way to genuinely verify their work, they’ll just tell you it’s done. Give them Playwright and teach them to use it, and they’ll actually check.

In my specs, I include a “manual testing” section that describes exactly how to verify the feature. The agent reads it, does the verification, and reports back. It doesn’t catch everything, but it catches the “four working components that don’t work together” failures that used to burn me.

Letting go

I packaged this into a tool called BranchBox. It’s an open-source engine for spinning up isolated dev environments per Git branch. Every feature gets its own worktree, devcontainer, Docker network, database, ports, and tunnels. No collisions. No shared state.

I’ve been running this setup for a few months now. For the first time, I can actually use YOLO mode.

I kick off an agent. I point it at the spec. I walk away. I come back to work that holds up. Not always—the agent still makes mistakes. But when it breaks things, it breaks them in a container I can throw away. The blast radius is zero.

YOLO mode only works when YOLO can’t hurt you.

What’s next

I’m still refining this. The patterns keep evolving.

Throughout December, I’ll write more about specific pieces: automating tunnel provisioning, structuring the docs/backlog workflow, teaching agents to verify with Playwright.

If you’re building something similar, I’d love to hear what’s working. And if you want to try BranchBox, it’s on GitHub.

The model isn’t the bottleneck anymore. The environment was. Once I fixed that, I could finally stop babysitting and start shipping.