For about a year, I avoided giving agents real permissions. Not because I doubted their utility, but because I didn’t trust the blast radius. If an agent can’t do anything meaningful, it’s a toy. If it can do everything, it’s a liability. The useful zone is the uncomfortable middle: enough capability to do real work, inside an environment that is aggressively constrained.

OpenClaw is what finally got me across that line. If you haven’t used it, think of it as one operational surface for agent CLI execution, browser control, scheduled jobs, and chat-based control loops. Its bet is CLIs over MCP servers. Agents handle text-based back-and-forth well, and the context cost is way lower than JSON tool schemas.

But OpenClaw’s default setup assumes a dedicated Mac. People were buying Mac Minis just to give agents a full box to run on. That makes sense for Peter Steinberger, who built it and comes from the Mac ecosystem. He sees where AI is going and ships toward it while most people are still debating whether it’s real. OpenClaw exists because he didn’t wait for consensus.

But my setup is Docker-first. I wanted disposable boundaries I could reason about and reset.

Getting it running

I found a Docker setup via a Simon Willison post. It didn’t work out of the box, but after some fiddling I got the container up.

I tried WhatsApp as a control channel first, went down a Canadian eSIM rabbit hole, and backed out when the cheapest burner option was $15/month. Telegram connected in minutes and has been solid since.

For dashboard access, I ran Tailscale as a sidecar container instead of the default daemon-inside-the-container setup. That gave me access from any device on my tailnet with no public endpoints. No “temporary” internet-facing holes. No accidental permanent ones.

The plumbing was the easy part. The hard part, it turned out, had nothing to do with infrastructure.

The real problem was identity

I didn’t want to give the agent my credentials. I also didn’t want some personal super-token sitting in a script. Every agent setup I’d seen solved this by loading secrets into the environment at startup and hoping for the best.

I went a different direction: I gave the agent its own identity.

I created a new email account on my company’s domain. Set up 2FA. Stored everything in 1Password, but not in my vault. I created a separate vault just for the agent, then set up a service account with read-only access to that one vault.

The agent uses the 1Password CLI to fetch secrets at the moment it needs them, not at container startup. If I want to cut the cord, I revoke the service account. Secrets aren’t cached in memory. They’re not baked into the environment. They’re just-in-time.

That decision shaped everything that followed.

A browser that doesn’t look like a bot

The default OpenClaw browser setup expects either headless Chrome or one with a specific extension installed. Neither worked for what I needed.

Headless Chrome, specifically the stripped-down headless-shell image most people reach for, ships with HeadlessChrome in its User-Agent string. Sites like X detect that immediately. It also lacks browser APIs that bot-detection scripts test for and doesn’t support persistent sessions. Every visit looks like a first visit from a suspicious client.

So I built a Chrome sidecar running full Chromium in headful mode by default, with Xvfb and noVNC so I can watch the agent’s browser sessions live. I added --disable-blink-features=AutomationControlled to suppress the automation flags that detection scripts look for. And I mounted a persistent user-data-dir so cookies, sessions, and local storage survive restarts. Returning visitors get treated differently than new ones, and that matters.

Because it’s on the tailnet, I can pull up the browser from my phone and see exactly what the agent is doing. That turned out to be less of a debugging convenience and more of a safety control. If I can’t see what’s happening in the browser, I can’t claim the system is controlled.

I can switch to headless mode when I need the performance, but headful is the default. I’d rather have visibility than speed.

Don’t trust the defaults (even the skills)

This might be the most paranoid part of my setup, but it’s also the part I’m most convinced is right.

OpenClaw ships with built-in skills for common tasks: web search, browser interaction, 1Password access. I didn’t use them. Instead, I had the agent build its own versions from scratch.

For 1Password, I wanted a skill that uses the OP CLI with just-in-time access through my scoped service account, not whatever default auth path the built-in skill assumes. For web search, I wanted it hitting the Brave Search API with a key fetched from the vault at query time. For browser interaction, I wanted it talking directly to my Chrome container’s CDP endpoint, not routing through OpenClaw’s relay extension.

The philosophy is simple: if I’m going to trust a tool, I want to understand exactly what it does. Having the agent generate the skill from a clear spec means I can read it, audit it, and know the full surface area. Built-in skills are someone else’s opinions about defaults. My defaults are my own.

Is this slower to set up? Yes. Do I sleep better? Also yes.

CAPTCHAs, OAuth, and the shortcut hiding in plain sight

Then I pointed the agent at X for market research. X’s API access is locked down hard. Peter had built a skill called Bird for browser-based X access; he had to take it down days ago. Browser automation on X has been getting harder too.

So I told the agent: just use the browser. Go create an X account.

It couldn’t. CAPTCHAs.

Then I realized something that turned out to be the key to most of the agent’s web interactions: half the internet supports Google OAuth for signup. The agent already had a Google account with working credentials and 2FA in its vault.

I told it to sign in with Google. A couple of minutes later, it had an X account.

That pattern repeated everywhere. GitHub? Same thing. CAPTCHA wall, Google OAuth, account created. I added the agent to my blog’s repository, and now it can open PRs under its own identity.

I’d been thinking about CAPTCHAs as a technical blocker. They were an identity problem. Once the agent had a real, scoped identity with standard auth flows, a whole class of obstacles just disappeared.

The boring automation that proved the system

Before I pushed on anything ambitious, I built email triage. Check the inbox every five minutes. Implement inbox zero. Summarize what matters. There’s an allow-list, so not anyone who discovers the email address can trigger actions.

It’s boring. That was the point.

If a system can reliably handle auth, periodic execution, sensitive input, and predictable output day after day, it’s not a demo anymore.

The workflow that actually matters

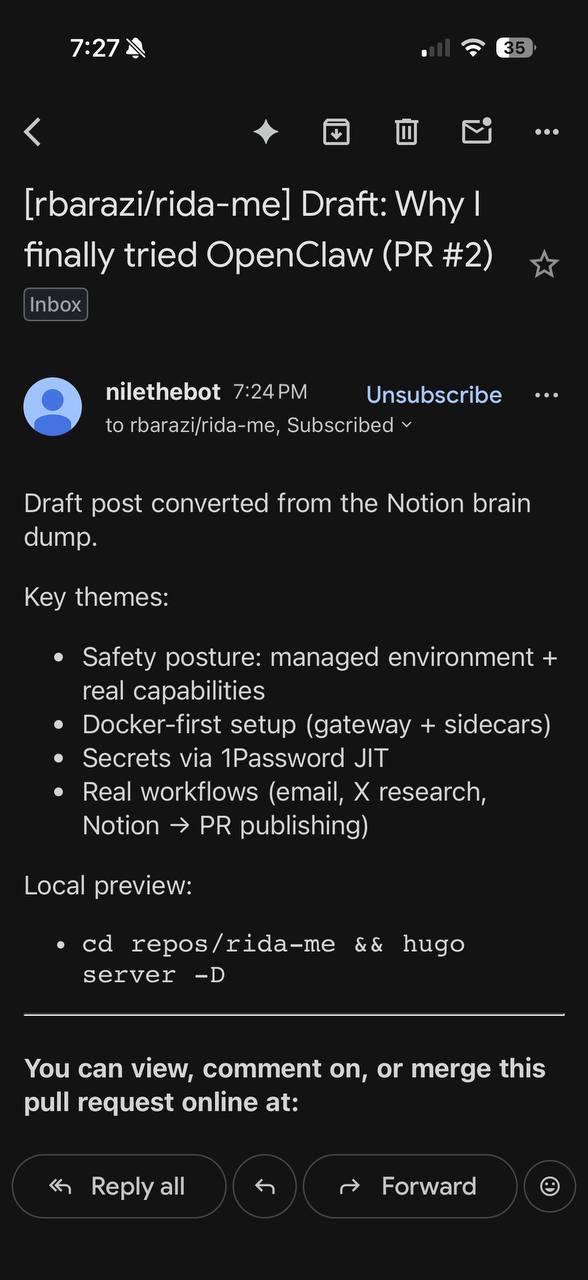

Email triage and X research proved the system worked. The Notion-to-blog workflow made me want to keep building.

The loop: brain dump in Notion, shape the draft with the agent, open a PR against my Hugo site, review the Cloudflare Pages preview, iterate, publish.

What surprised me wasn’t the writing output. It was the handoff quality.

I got a PR from a scoped author identity, with a real diff, a working preview URL, and a clear path to merge or reject. I could review it like any other engineering contribution. Not a demo transcript. A reviewable deliverable.

In fact, this post is the proof. I dictated the first draft as a voice memo, transcribed it with MacWhisper into Slack (another channel the agent monitors), and the agent created the Notion draft. We collaborated on it. When I gave the thumbs up, it opened the PR. I reviewed the preview, said publish, and it merged.

If you’re reading this on rida.me, the whole pipeline worked.

The threat model I should have written first

I wrote the threat model after I’d already made most of the architecture decisions. That’s the wrong order. But writing it retroactively clarified why those decisions felt right, and I’d recommend anyone doing this write theirs before they start.

I kept it simple: what can go wrong, who’s likely to cause it, what failures I can accept, and which ones I can’t.

Likely adversaries: Mostly me. Misconfigured permissions, bad defaults in scripts, automation drift, prompt injection in web content. My posture on prompt injection is pragmatic, not solved. I treat web content as hostile, keep permissions narrow, and gate high-impact actions.

Acceptable failures: tasks that need retry, timeouts, manual intervention.

Unacceptable: unscoped secret exposure, unauthorized external actions, host-level persistence from agent behavior.

| Risk | Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Credential exfiltration | Scoped 1Password vault + service-account reads only |

| Network abuse | Tailnet-only access, no default public exposure |

| Arbitrary host damage | Containerized execution with explicit mounts |

| Rogue browser behavior | Isolated browser container + observable runs |

| Silent false-positive success | Verification loops + run-level spot checks |

In practice, the boundary is simple: scoped secrets and reversible automations are in. Broad personal tokens, unrestricted host actions, and irreversible external actions stay gated. It’s not bulletproof, but it is explicit. And explicit beats vibes.

What went wrong on the way to this post

Publishing this blog post was supposed to be the clean proof that the pipeline works. It mostly was. It was also the best stress test I could have asked for.

The agent opened the PR, and the Cloudflare Pages preview URL looked right. I clicked it. Blank page.

Under the hood, three things had gone wrong at once: a stale deploy hash from an earlier build, a browser-control timeout during the verification step, and an old Hugo template override that only surfaced in the newer build path. Each one was minor. Together they produced a confident-looking link to nothing.

I told the agent “don’t come back until this is actually working.” It took three branch updates (merge from main, remove a dead Google Analytics partial, fix draft visibility settings), four preview URL checks, and about two minutes of wall time after I stopped being patient.

The PAT in the service-account vault also didn’t have the visibility I expected, which meant the agent hit GitHub auth friction mid-flow. That was a configuration error, not a system failure, but it’s the kind of thing that only shows up when you run the real workflow end to end.

None of this was catastrophic. All of it was instructive.

This is why I treat observability as part of the safety boundary, not just debugging hygiene. If I hadn’t been able to trace exactly what went wrong, I’d be left guessing whether the system is trustworthy.

Where it still hurts

Browser-control flakiness is the biggest operational drag. When timeouts hit, throughput drops and you’re forced into retries.

But the real long pole is identity. Auth flows, token lifecycle, credential scoping, access auditing. Once you leave toy workflows, identity design dominates implementation design. The model is rarely the bottleneck. The question is always: who can access what, when, from where.

And agent output still needs verification. These systems are optimized to complete tasks, not to prove outcomes.

“Done” is not a safety property.

What I’d write on a whiteboard

The hard problems of agent automation are identity problems.

Design for containment first. Then optimize for autonomy.

If an agent can surprise you, the environment is under-specified.

OpenClaw didn’t convince me because it looked powerful. It convinced me because I could contain it.